Today I learned of the death of the artist-mystic Meinrad Craighead at the age of 83.

Born Charlene Marie Craighead in 1936 in Arkansas, she lived a remarkable life, teaching art in Albuquerque, then Italy and Spain, before spending fourteen years as a Benedictine nun in Stanbrook Abbey in England. It was there that she took the name Meinrad, after her mother’s great uncle, who had been a monk in Switzerland. (He is said to cure people.) In 1983 she returned to the US, settling near the Rio Grande in Albuquerque.

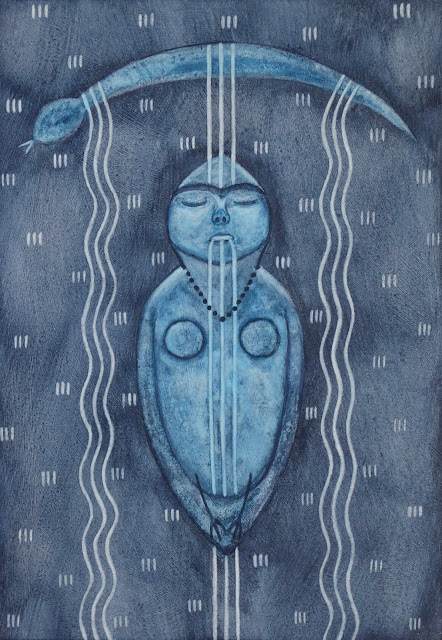

|

| The Moons of the Vernal Equinox (from The Litany of the Great River, 1991) |

It is only in the past year or so that I have discovered Meinrad’s art, and watched the short videos made by Amy Kellum, Praying with Images and God Got Bigger, which I know I will continue to return to whenever I am feeling particularly uninspired. They do not fail to invigorate me, to show me what is possible, to make me want to keep seeking, keep trying, to be receptive and ready, and to create from that vast space of openness.

Though Meinrad seemed a small, unassuming woman, she was intimately connected with the wild, with the spirits of animals and the land around her, and the often overwhelming nature of God the Mother, who is certainly not just sweetness and light. Her work is beautiful, strange, and sometimes confronting in it’s depiction of birth and death, dream and transformation. It links spirit, woman and nature into a seamless weave of divine immanence.

|

| Crow Mother Over the Rio Grande (from The Litany of the Great River, 1991) |

What I also love about Meinrad was that her studio was a shrine, and her art practice was ritual. Her approach to her work, as a sacred calling, as a communication with the many spirits she was in contact with, is an inspiration.

She wrote:

My personal vision of God the Mother, incarnated in my mother and her mother, gave me, from childhood, the clearest certainty of woman as the truer image of Divine Spirit. Because she was a force living within me, she was more real, more powerful than the remote Fathergod I was educated to have faith in. I believed in her because I experienced her.

…

I draw and paint from my own myth of personal origin. Each painting I make begins from some deep source where my mother and and grandmother, and all my fore-mothers, still live; it is as if the line moving from pen or brush coils back to the original Matrix. Sometimes I feel like a cauldron of ripening images where memories turn into faces and emerge from my vessel. So my creative life is itself an image of God the Mother and her unbroken story of emergence in our lives. (From the introduction to Meinrad Craighead, The Mother’s Songs: Images of God the Mother, Paulist Press: Mahwah, New Jersey, 1986)

I feel so lucky that I have two of her books (which are mostly out of print and difficult to find). I will treasure them and remember Meinrad every time I return to their pages for inspiration and guidance.

Farewell, Meinrad. Journey well on the next stage of your being.

|

| Throne (from The Mother's Songs: Images of God the Mother, 1986) |