Ts’its’tsi’nako, Thought-Woman,

is sitting in her room

and whatever she thinks about

appears.

She thought of her sisters,

Nau’ts’ity’i and I’tcts’ity’i,

and together they created the Universe

this world

and the four worlds below.

Thought-Woman, the spider,

named things and

as she named them

they appeared … (1)

* * *

Earth-Thinking

I find myself thinking about the nature of thinking: What is thought? How should we think?

Part of this line of enquiry has come about because of meditation—or, more specifically, the lack of it in my life—over the past year or so. It has become a troublesome concept, no longer a beneficial (or at least neutral) practice, but one tinged with complexity, and ideas that make me feel uneasy; and so I have been avoiding it.

We are often told to stop thinking when we meditate, or at least not to cling to thoughts as they pass by. Thinking is so often seen as the enemy, the thing to be controlled or conquered on the way to experiencing a ‘proper’ meditative state, some kind of ‘thoughtless’ spaciousness or emptiness.

Many spiritual traditions also see thoughts as a problem, particularly the stories we tell and believe about ourselves and the world, relegating them to ‘ego constructs’ and thus mere illusions.

I find myself reacting strongly, quite viscerally—that is, bodily—to these ideas. I wonder why; and then I think and think and think, and eventually write, trying to make sense of things.

The thing is, I don’t believe that thoughts or stories are illusions. I believe that they are the sensuous fabric of reality. However, this doesn’t mean that all thoughts and stories are equal. Some are clearly damaging, or at least incorrect. We can, for instance, get stuck in very restrictive personal stories, continually living out the same old patterns, and never progressing beyond. It is only when we shuck off those limiting stories and retell our lives in new ways that we can grow as people. Yet in this instance we move from one story to another, from one that is old or no longer needed, to one that is new and helpful. One story naturally evolves into another—without beginning, without end.

Stories are necessary. The creative process of Life manifests itself through a myriad of stories—cosmic, earthly, human, nonhuman, geological, biological, and so on. Thus, in a completely real sense, stories are what the universe is composed of. Story moving to story—thought to thought—events occurring—evolution taking place—death following life following death leading to rebirth …

The task is not to eliminate these thoughts and stories, or to stop ourselves from thinking, but to learn how to discriminate between good thoughts and bad; between true, helpful stories and untrue, harmful ones. Thinking is not inherently bad—it is ‘distorted’ thinking that is the problem.

So how do we know when thoughts are distorted, or when they are correct?

The way to do this is to compare and align our thinking with what is, the real world around us—the earth, and the processes of Life. Thoughts that cleave to earth-reality are, in general, true thoughts, arising from the land and our interaction with it. These are thoughts woven into the wildness of the world, and inseparable from it. These thoughts possess a naturalness, an organic morality and beauty, an integrity. They may be thoughts or ways of thinking that are human/cultural, yet they respect the connection of the human with the earth, and do not attempt to sever or ignore this bond.

Distorted thoughts or ways of thinking have broken their connection with the earth—either from an ignorance of its existence or need; or by a deliberate attempt to transcend the realities of what is, in an arrogance stemming from a belief in human superiority. This is the current (and longstanding) situation in the Western world, at least, if not increasingly elsewhere.

But if we thought ourselves into this mess, we can surely think our way out, by returning our thoughts to their rightful habitat—the earth—physical reality itself.

So, the questions we need to ask are: How do we realign our thinking processes with the earth?—which is where our thoughts ultimately stem from, after all. How do we make our thinking wild once more?

It is the process of discrimination that is the hardest part—knowing when a story is true, and when it is not; when it is earth-given and natural, and when it is an anthropocentric distortion. The ways we are taught to think (or not) in this culture; the ways we are forced away from what is, and what is right, towards ways of living that are separate from the earth—these things limit us, and give rise to distorted thought after thought that lead nowhere, and result in nothing good.

Woman-Thinking

I’ve been thinking these thoughts for some time—thoughts that want to be thought—and struggling to find ways to articulate them; as well as struggling to find ways to refute the negative views on thinking, that repel me so physically, whilst also making it clear that some thoughts are indeed harmful.

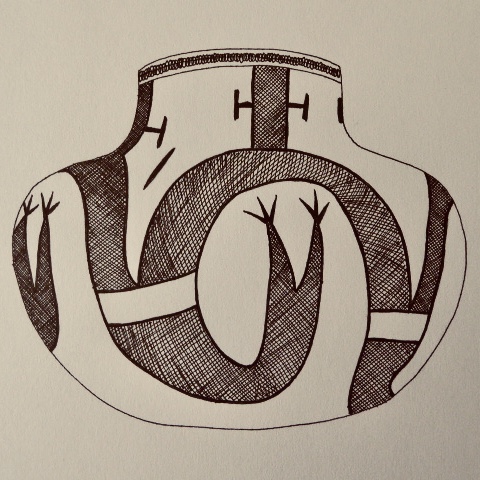

My ideas have been helped along by reading the work of two ecofeminists: Jane Caputi and Charlene Spretnak; as well as the wisdom of two indigenous writers: Leslie Marmon Silko and Paula Gunn Allen. For their sharp-witted, gynocentric knowledge, I am grateful. As I am also grateful to the creatrix of the Southwestern Pueblo Indians—Thought Woman (also known as Grandmother Spider), ‘who thinks and dreams and spins the world into being’ (2). Caputi writes:

As Paula Gunn Allen explains, “The thought for which Grandmother Spider is known is the kind that results in physical manifestation of phenomena: mountains, lakes, creatures, or philosophical-sociological systems.” Unbalanced, phallocentric thought, on the other hand, results in the physical manifestation of phenomena such as social inequality, pollution, nuclear weapons, genocide, and gynocide. (3)

This is an important distinction to make: there is balanced, generative thought (characterised in this instance as female); and then there is the unbalanced, destructive kind (characterised as male). Both types result in the creation of physical reality, yet it is clearly the former that should be focused on.

Spretnak elaborates further on this idea. Referring to the work of Claudine Herrmann who analysed the ways men tend to operate linguistically within the systems they have created, she writes:

Man generally prefers himself to what surrounds him, to the extent that he places his mental categories before those of objective reality. His structures of thinking are external to him (and are entirely foreign to women); he is, therefore, stunned by everything and seeks to impose control over it … Moreover, every man has a tendency to organize the world according to a system in which he is the center. Men’s space is a space of domination and hierarchy, of conquest and expansion. (4)

On the other hand, women think differently, having a talent ‘for grasping the gestalt, or big picture, in any situation, as well as for perceiving an awareness of the dynamic interrelatedness that is involved’ (5).

I want to make it clear now that I am not saying that all men think as the above quote suggests, or that women don’t or can’t think in that way also. (Also, I am not suggesting that that form of thinking is innate to men, or the way they have always thought.) However, there are specific differences and tendencies that have been found to exist in men and women, and this is important to point out, seeing as the masculine way of thinking is the norm, and women are expected to conform to it. It is what we are taught, whether we feel comfortable with it or not; and it is what has shaped the structure of our culture, to our detriment.

What particularly interests me about Spretnak’s quote is that Man ‘places his mental categories before those of objective reality’—that is, he ignores what is in favour of what he wishes to be—his own, necessarily flawed, perspective of reality. This is precisely what has come to my attention over the past year or so: the Western/masculine/postmodern flight from the Real, in favour of some humanly constructed realm of ideas, which lacks both meaning and material reality.

Thus, my ideas about thought are gravitating very much towards both a female and an embodied stance. Importantly, gynocentric thought is subjective, and rooted in personal, embodied experience, in contrast to the masculine objective point of view. Yet the very crucial difference is that the subjective experience of women tends to be very firmly attached to what is, rather than the flawed view of reality that ‘Man’ tends to hold. (Thus, though men pride themselves on their rationality, their thoroughly objective and empirical view of reality, the truth is in fact quite the opposite. They have so distanced themselves from the Real that they can no longer see it as it is, and therefore their thinking rarely reflects what is.)

Body-Thinking

Except perhaps in the case of Thought Woman (and perhaps not even then), thoughts do not emerge from nowhere. For embodied beings thoughts arise due to our immersion in and interaction with the world around us, so thoughts are a physical phenomenon. (This idea of embodied cognition seems to be becoming more common.) Thus, if thought originates in the material world, and our felt experience of it, it would be true to say, as Carol P. Christ does, that ‘Feeling is the origin of thinking’ (6). Thinking, at its root, stems from sensation, sensuousness.

What Christ also means is that thoughts are not separate from feelings—instead, they work together, intermingle. There is no such thing as pure thought, no such thing as pure feeling, only a combination of the two.

At some point in our human evolution, conceptual and discursive thought came into existence. This is the kind of thought that tends to dominate in modern humans. Yet it was different for our ancient ancestors. As Reginald A. Ray says, in relation to hunter-gatherers:

Conceptual thinking plays an important role, but it is very much in balance with the more somatic functions, and also serves them—thinking is embedded in and is in service to the interpersonal and natural worlds accessed through sensation and feeling. (7)

While I do agree with Ray, I think he is only half right. Thinking is (or should be) embedded in and in service to the world of sensation and feeling. Yet I think it goes both ways, for feeling is also embedded in and in service to thinking.

Ray goes on to say:

Thinking … tends towards disembodiment: it separates in that it involves a disengaged stance whereby—based on past experience—we abstract from the living and invaluable other, think him as an object, ignore him as an independent actor, conceptualize him, and consider how to manage our relation with him. It is cool, apart, and noncommittal—in other words, disembodied. Thinking, when it stands as the primary or sole function of interrelation with the other, leads us, in the words of Martin Buber, into an “I-it” rather than an “I-thou” relationship. The most important human cognitive function since the invention of agriculture, thinking has come to be more and more predominant, while the other functions or ways of knowing have, in many modern people, atrophied. (8)

Again, I believe this is only half true. Most of us modern people (myself included!) are mired in a kind of abstract, typically verbal, thought that is very disembodied, and this is a major problem. Yet since all thought is connected with feeling and physical experience, I don’t think we can say that it is truly disembodied, only that we perceive it as such. Or, our thinking is disembodied in the sense that we are denying or numbing our feelings, denying the reality of our embodiment, and this gives rise to distorted, untrue thinking.

Interestingly, the ‘objective’ kind of thinking that Ray is discussing sounds very much like the ‘masculine’ objective thought that Spretnak spoke of. Thus it is only one kind of thinking, the one that has come to dominate over the somewhat different ‘feminine’ subjective thinking, which is not ‘disengaged’, not ‘cool, apart, and noncommittal’, and not an ‘I-it’ relationship at all.

So the problem, I believe, is not thinking as such, but the separation of thinking from feeling and the physical world. After all, in order to write this essay I have needed to think in abstract and discursive ways. I have needed to think rationally, to structure my words and ideas so that they make sense. Humans are thinkers, and this is natural. We also use language, which is also natural (at least in oral form, as writing is optional). But what I have written has come about because of what I was feeling. I felt there was something wrong with certain views on thinking. I felt uncomfortable. I feel in my body that there is a very real problem here, and thus my feelings have inspired my thinking, my thinking has been born from my feeling.

The problem in so many areas is that of separation: mind from body, culture from nature, spirit from matter, thought from feeling. Reconnection is the key.

I will remain a thinker. I will not try to silence my thoughts. Instead, I intend to be mindful of what I am thinking, what purpose my thoughts serve. If my thoughts cease to flow, if I get stuck in rumination or thoughts that cause distress, I will drop down into my body, seek those feeling-thoughts, sensation-thoughts, or a communicative wordlessness that brings me back to a deeper way of knowing. This, I think, is the kind of meditation I wish to engage in—an embodied, somatic kind.

Further, I like the idea that meditation be not about silencing thoughts altogether, but silencing our very limited, mundane, objective and distracting human thoughts, in order to open the ears of our hearts to the nonhuman voices around us, to the thoughts of the earth, to a language older than words (to use the title of one of Derrick Jensen’s books). David Abram says that we should

[turn] aside, now and then, from the churning of thought, dropping beneath the spell of inner speech to listen into the wordless silence. Only by frequenting that depth, again and again, can our ears begin to remember the many voices that inhabit that silence, the swooping songs and purring rhythms and antler-smooth movements that articulate themselves in the eloquent realm beyond the words. Only thus do we remember ourselves to the deeper field of intelligence, to the windblown thinking that is not ours, upon which all our thought depends. (9)

Connecting with and listening to this ‘deeper field of intelligence’ is essential for the creation of our own thoughts, ideas, feelings and creative works. In a sense, we do not think ourselves, but are thought by the world. Thought by Thought Woman herself.

Love-Thinking

There is yet another way to look at thinking that I have come across, and that is thinking as thanking, thinking as love. David Hinton writes

… we can trace [the word] think far enough back to see that it converges at its vanishing point with thank in the Indo-European tong-, which means love. So it seems likely that thinking was early on experienced as gratitude or love for the world. (10)

Thus, thinking is not and has never been inherently bad. We must simply strive to have the right kinds of thoughts, engendered by a love of what is.

And because thoughts and stories do literally influence and create our world, we need to be very careful about what we are thinking: whether it is balanced, generative, and based on love; or unbalanced, destructive, and based on hatred.

We must ask ourselves: What are we thinking about? What does our thinking serve? What does it result in? What stories are we telling?

If thought is rooted in a love of what is, in embodied truth, then, however flawed our thinking may sometimes be, it will rarely be ‘wrong’ or harmful.

The way we think can change, can flow into something new, can reconnect with feelings and the physical. We can begin to reject harmful stories and tell more fruitful ones, in the knowledge that even those stories will change, go backwards on occasion, spiral back over old ground. But they will keep being told, regardless of where we are headed, for they are what the universe is made of.

We must also remember that it is not just humans who think and tell stories. The earth thinks. The earth tells tales. We are thought by and through Her, and we participate (either well or badly) in the telling of the tale of Life.

I wonder how we can return to thinking as thanking, to truly embodied thought—thinking that may or may not be verbal—and I think of how the earth once spoke through humans in myth, in the earliest poetic utterances—through a sense of awe and an awareness of beauty. I think these are good places to start, in myth and poetry, to get a feel for how the earth thinks and dreams, and of what we need to know. Writing and speaking in these forms brings us closer to the roots of language, the roots of human culture, and the primordial nature of the land.

Art is another place in which the earth speaks—through imagery rather than words, particularly in symbols. This may well be even closer to how the earth naturally communicates.

I also think of women’s cultures—of the creations and crafts, wise ways of speaking and thinking, of women, and I want to take part, in my own way.

Myth. Poetry. Art. Symbol. Dream. Feeling. Love.

If we think, speak, write and create in these ways in order to show gratitude, we give much-needed gifts back to the earth.

I refuse to believe that thinking is the enemy. And I refuse to be forced to think in the dominant way, however hard it is to break free of it. We must find other ways. We must think, speak and act thoughtfully, combining the rational with the intuitive, the logical with the mythopoetic, words with images and visions. We must return to the body and the earth as the origins, the roots of our being.

Thought Woman gave us thought. She meant for us to think, and to give our thoughts back to Her in thanks, so we must use our thinking capacities well, and gratefully. And in particular, we must respect the thinking and speaking of women, for

It is as the old ones have told:

the name of the Female Principle is “Thought,”

and she is more fundamental and varied

than time and space. (11)

What are your thoughts?

References:

1. Leslie Marmon Silko, Ceremony, Penguin: New York, 1977, p. 1

2. Jane Caputi, Gossips, Gorgons & Crones: The Fates of the Earth, Bear & Company, Santa Fe, 1993, p. 202

3. ibid, p. 78

4. Charlene Spretnak, ‘In the Absence of a Mother Tongue’, Women’s Voices: A Journal of Archetype and Culture, Spring Journal: New Orleans, Louisiana (Fall 2014), p. 87; you can download a copy of this essay here: http://www.charlenespretnak.com/events.htm

5. ibid, p. 91

6. Carol P. Christ, ‘Woman and Nature: Our Bodies Are Ourselves’, 26 June, 2017, Feminism and Religion, https://feminismandreligion.com/2017/06/26/woman-and-nature-our-bodies-are-ourselves-by-carol-p-christ/

7. Reginald A. Ray, Touching Enlightenment: Finding Realization in the Body, Sounds True: Boulder, Colorado, 2008/2014, p. 36

8. ibid, p. 39

9. David Abram, Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology, Vintage Books: New York, 2010, p. 178

10. David Hinton, Hunger Mountain: A Field Guide to Mind and Landscape, Shambhala: Boston, 2012, p. 57

11. Paula Gunn Allen, in Caputi, p. xx