In aid of my unlearning and unforgetting, I’ve been taking part in Sylvia Linsteadt’s Witchlines Study Guild, in which we are exploring the pre-patriarchal, Neolithic cultures of Old Europe. The studies are centred around the multi-disciplinary ‘archaeomythological’ work of eminent Lithuanian archaeologist, Marija Gimbutas (1921–1994). As Sylvia writes:

At the center of this study guild is my belief that the native witchcraft traditions of Europe are a late manifestation of an ancient, indigenous, earth-based culture that predates the arrival of Indo-Europeans during the Bronze Age, and finds its roots far back in the culture that archaeologist Marija Gimbutas calls Old European (which spanned roughly 7000 to 3000 B.C.E.), and likely even earlier, in Paleolithic and Mesolithic traditions.

…

Together we will be following the tenuous pathways that lead us back to the roots of a culture in which reverence for the web of life and a feminine divinity (in many diverse manifestations) were valued at the center of European culture. My hope is that this journey into the deep past can inform our present, and hopefully our future, in a time when the Earth is more and more in need of those who would revere the sanctity and regenerative powers of the natural world, and each other. (https://www.witchlines.net/about)

This is a subject and a cause that I feel very strongly about, for I am sure that beneath the accreted historical layers of our destructive modern culture, lies something old, wise, and entirely different—a matrixial culture that was born from and existed in reverence to the earth. For those of us of European descent, this culture is part of our indigenous heritage, which for far too long has been lost to us.

Though much controversy surrounds Gimbutas’ work, what she unearthed through archaeological excavations, and the study of linguistics, folklore and symbols, is of vital importance. It also seems to be gaining more and more acceptance, especially now that one of her main detractors, Colin Renfrew, has conceded that Gimbutas’ ‘Kurgan Hypothesis’ is indeed correct.

I hope that what I learn as I go in search of the witchlines that bind us to the earth will both inspire me creatively, and teach me more about how best to live—bringing reverence back to a world characterised so much by irreverence.

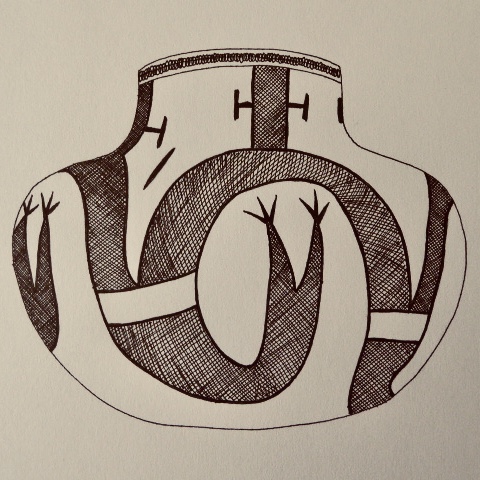

The course work includes creative writing exercises, which I plan to share here. The first of these was inspired by a drawing of a pot/vase found in the pages of Marija Gimbutas’ The Civilization of the Goddess (1991). Below is my own drawing of it, and the story that emerged of its making.

The Vessel Filled With Time

Round-bellied, full and heavy, lined with time’s marks. Her sides bulge. Each mark is a word, snake-tongued, flickering like fire, spurting sap. In clay is breath of snake, breath of mountain, exhaled. Earth, water, fire and sparks of light.

Her quick old hands are slick with clay, grit between her fingers, and she sings as she works at the shaping, the stroking into being of a new vessel. Love lives under her skin and in whatever she sees, whatever she touches. Her own daughter has a child now: so she is now a mother’s mother, an old one, blessed by time. She knows well the way of the making—in love, and life—and her hands move, building coil on coil, smoothing, rounding the form up and over and to its lip.

A child peeks in at the door, dark eyes quiet and shining, wondering at the house of clay, at the old woman sitting in the shadows, humming as she works. A spirit crouches by the door also, and in the shadows, looking upon the women, the child, the vessels made whole, made from earth, called forth to be formed, marked, transformed, held.

The old woman ceases her singing and smiles at the little girl, and the presence she can feel but cannot see, except in the making. That presence has always crouched there, gentle and attentive, beckoning songs from the women, from the clay. It fills her hands with knowing, with a shape that is good.

When the vessel is made, the child gone to play, and the spirit has enlarged to fill the room, her body, the woman begins to sing again. A different song this time—lower, softer; wordless, yet speaking. She lifts her tool and begins to mark the soft surface of the clay, to carve lines into its flesh: snake, tongue, mountain, river, tree, breast, milk, womb, soil, time.

There is no time—only the song, the making.

Light shines through the door and moves across the floor, and the song ends, trailing off the woman’s breath and back to the air from which it came. The inscription is complete, and as the woman rises, she stretches out her spine, loosens her stiffened knees. The vessel is taken to the kiln, and she prays for its safe transformation, its journey to change substance—soft to hard, shapeable to shaped. Born anew.

And from its heavy, round belly a voice will then speak:

Her mountains taste the air. Her mountains spill forth their milk into the sky and across the land. The snake coils and uncoils from her spiral, her knowing centre, and she is time, earth-born, bearing gifts of life. In her body you grow, become; and in her circling arms you will sleep.

Live well, and give gifts of beauty to the one whose name is Earth.

your vision of the pot-maker and all about her is so wonderfully peaceful. i could feel the unhurried, calm communion of the woman with the spirits, and the joyful tranquility of being one with all that is...

ReplyDeletei first studied gimbutas' work two decades ago, and i am very happy indeed to see it is having a resurgence now. she was a great mind, and her perspective on old europe has much to offer us. now more than ever, perhaps.

Thank you. I'm so happy with my little tale.

DeleteAnd Sylvia is offering a wonderful thing with the Witchlines course. So vital for these times. I am learning a lot.

Such an evocative, earthy, female-centered tale. I like it very much! Intrigued by the Witchlines course, and I am not familiar with Gimbutas's work so thank you for the signposts! On one hand I believe a culture cannot be separated from the land that gave rise to it and truly "make sense" as a living tradition...but on the other hand, even to learn of such cultural remnants may strike chords that are more universal and translatable across time and land.

ReplyDeleteThank you, Carmine.

DeleteI agree that cultures should arise from their own landscapes. However, since most of us have lost the connection with our own places (and with true culture itself), it is important to look to those cultures that maintained it, for inspiration and advice. What's more, Gimbutas claimed that Old Europe was made up of societies that were egalitarian, peaceful, and connected with the earth, in which women held high status—and that thus provide an alternative vision for what society can be like. That's part of the reason so many people criticised her and her work—they could not see beyond patriarchal and dominating forms of culture; and perhaps they were frightened by the possibility of a different kind of world, in which the earth was revered. Indeed, Old Europe has many similarities with other indigenous cultures around the world, particularly in its reverence for the processes of life and regeneration, so it does strike chords that are universal, and entirely necessary, I believe.

Such a wonderful tale, beautifully written.

ReplyDeleteI love Gimbutas' work and the ancient wisdoms she discovered. And while I agree with Carmine that culture can not be separated from the land, I also think most lands are speaking the same thing, and all that differs is the language they use - sand or pine or sea or fire - and the language we use to reply. Underneath dialects, the message is surely the same. Treasure life, respect all living things and their place in the web of being, and be Love.

Thank you, Sarah.

DeleteYes, just that! In learning about Old Europe we are learning about a culture that respected life and the web of being—and that applies to all places. It's also fascinating to see the similarities between, say, the Goddess figurines found in Old Europe, and those of indigenous America, or Japan. The earth really does speak the same thing, just with slightly different place-based dialects. I also think it quite important for those of us living in colonised lands, that we develop our own way of relating to the land (as opposed to just appropriating the perspective of the indigenous peoples), and part of that way of relating will be inspired by our ancestry. Further, Old Europe is a particularly rich source of women's history, which has been denied to us for far too long, and must be reclaimed.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete